How to teach writing to Grade 1 kids: New strategies for teachers and parents

Writing is a craft that is vital for both communicating and learning. However, many children struggle to learn to write. For most, their difficulties persist throughout elementary school unless they get help. As recently as 2018, there was very little research on how to teach Grade 1s effectively.

However, recent research shows how teachers can help Grade 1s make a strong start on writing. Parents have a vital role to play in laying a foundation for early writing success.

Many parents have likely heard children say, “I don’t know what to write.” Teaching children strategies for writing tackles this problem head-on.

Breaking writing down into steps

In 2019, a team of Spanish and British researchers published one of the first experiments on teaching writing strategies in Grade 1. They explored how a child can learn to write a story by asking themselves a series of questions: When did it happen? Where did it happen? Who is the story about? What did they do? What happened? How did it end? These questions help the child to generate and organize their ideas.

To help children remember this writing strategy, teachers in the study used a picture of a mountain with a path that led past six houses — one for each question. The teachers discussed the strategy, modelled how to use it and wrote together with the class. After instruction, the children wrote stories that were higher in quality, longer and more coherent.

Strategies work

The value of teaching writing strategies in Grade 1 has been confirmed by additional studies that examine teaching specific kinds of writing: Procedural writing (instructions for someone on how to do something), and opinion writing (short essays meant to persuade someone of something). In this writing research, teachers combined strategy instruction with discussions, picture books and dramatization.

And in our own recent research, we found that strategy instruction is effective for Grade 1 students across the range of writing achievement levels: low, medium and high. These Grade 1 studies join over 100 previous studies with students in higher grades in showing that teaching writing strategies works.

Printing, handwriting, spelling

Recent research also provides renewed support for the seemingly old-fashioned skill of printing. Grade 1s who can print accurately and quickly are able to create better and longer stories and reports. Teaching printing helps students to create better stories. Despite over 70 previous studies on the benefits of teaching printing and cursive writing, systematic teaching and assessment of these skills has declined in some curricula.

Read more: Writing and reading starts with children's hands-on play

Spelling is another traditional skill, the importance of which has been confirmed by recent research. Better spellers create better and longer stories, while poor spellers struggle with composing, and Grade 1 spelling affects the development of composition in later years.

Spelling education works best if it is formal, including, for example, lessons and practice activities. Additionally, teaching writing strategies combined with spelling and printing is more effective than teaching each of these skills alone.

Parents can help children practice spelling at home. Teachers and parents can also show children the “invented spelling” strategy of saying a word slowly, stretching out the sounds, and printing a letter (or letter combinations, such as “th”) for each sound. This will lead to some errors, but in kindergarten and Grade 1, invented spelling is an important driver of spelling development.

New understanding of Grade 1

This new understanding of the importance of Grade 1 is beginning to change writing education. In the past, many schools in Canada and the United States waited for struggling readers and writers to reach the middle elementary grades. Then, they were assessed by a school psychologist. If they were diagnosed with a learning disability, they were placed in a special education class.

However, in a new approach, response to intervention, teachers use evidence-based methods (like strategy instruction) to teach the whole class. They assess students regularly based on their daily writing, and if a child is below grade level, they receive help in a small group.

This approach is not yet common. However, it is almost certainly coming to some provinces in reading education. Reading education and writing education are intertwined, so we can expect the same approach to follow in writing.

Laying the foundations

The foundation for writing success is ideally being supported at home before children start kindergarten.

Parents can ask children to tell them stories, print the stories for them, then read them aloud for the child. They can teach children simple skills like forming letters and printing their name.

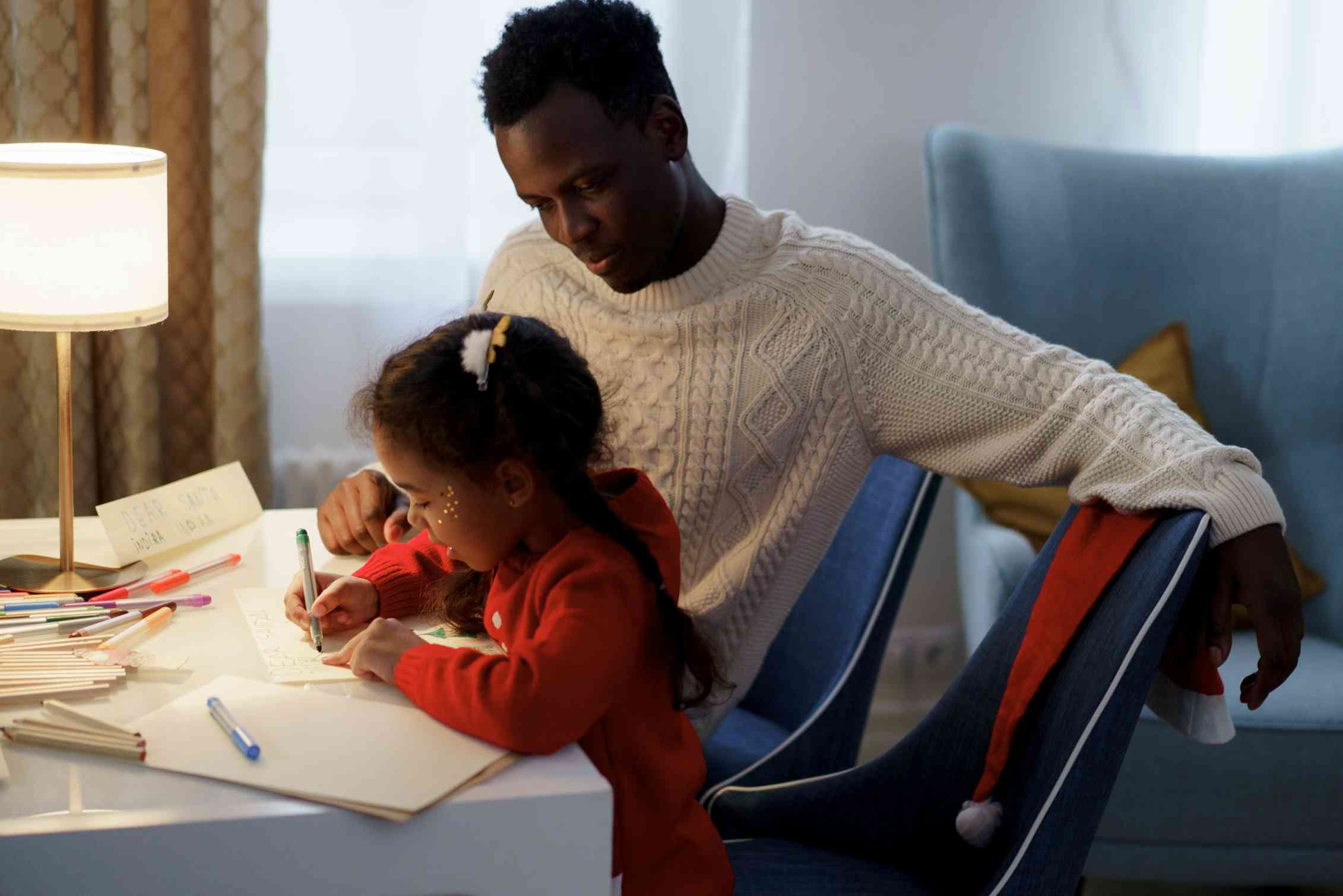

Parents can also practice printing with children at home; this is especially valuable for struggling writers. They can help children to write things that are important to them, like birthday cards for family members.

Read more: To help children learn how to read in the pandemic, encourage writing messages as part of play

Parents can also encourage children to read and write independently. Once children begin to write, parents can be their best audience, praising their efforts and the good qualities of their writing, and making suggestions to help with ideas, printing, and spelling.

When children begin school, and into Grade 1, parents can watch for red flags in their child’s writing development. During Grade 1, the average student learns to print the letters of the alphabet legibly and fluently, spell one syllable words the way that they sound (cat, game) and spell common short words that are not spelled the way that they sound (you, they). They also learn to write a story a few sentences in length about a personal experience.

If your child is missing these basic skills, don’t wait and see — talk with your child’s teacher and make a plan to help them succeed.

Perry Douglas Klein receives funding from The Social Sciences and Humanties Research Council of Canada