What The (Dixie) Chicks Meant to Me As a Teenager in Namibia

The last time I played “Wide Open Spaces” this much—75 times in the last year according to my iTunes Top 25 Most Played Songs playlist—I would have been approaching my early teens, 13 going on 14, when The Chicks were still called The Dixie Chicks. I was a classic teenager: energetic, temperamental, and feeling stifled by everything around me in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city, a place that could comfortably play home to the desire for escape encapsulated in the song’s opening verse.

Who doesn’t know what I’m talking about

Who’s never left home, who’s never struck out

To find a dream and a life of their own

A place in the clouds…

In the early 2000s, whatever happened to be cool in the world was lukewarm when it arrived in Namibia. Much like today, everything—food, fashion trends, monetary policies, and the latest slang—went through South Africa before it made landfall in my hometown. Blockbuster films aired at the local cinema a month or two late. Electronics of all kinds became expensive after import duties. Even the tourists who passed through the city seemed to do so only because they were either coming from or going to some other popular destination on the continent or in the world.

When my Rwandan family arrived in Namibia in 1996 after a brief stint in Nairobi, in Kenya, desperate to put kilometers between us and what would become an era-defining trauma, it seemed as though we, too, would eventually be on the move. In accordance with the immigrant theory of relativity—where e, being the energy needed to maintain migration, equals are-we-scared (which, in trauma migration, is always ) we were on the lookout for better, for elsewhere—any place that was home would do. Even as we were enrolled in kindergarten and primary school in Nairobi, my parents cast their eyes afield, beyond East Africa, as far away as our Rwandan passports and my parents’ university degrees could carry us. That is how we wound up in Namibia, a land of wide open spaces if ever there was any.

Shouldered by the ancient Namib Desert on the west coast and the thirsty Kalahari in the southwestern, Namibia is vast, sparse, and harsh. Short-lived rainy seasons and long droughts are its definitive features. Mountains and highlands break out in the interior. To the far north and north-east, where rainfall is more abundant and rivers are perennial, it can be tropical. To the far south, sun, sand, sky, and stars are draw cards—the landscapes are dramatic and possess a bleak beauty about them. In the middle of this country with one of the lowest population densities in the world is Windhoek—“the windy corner.” When my family settled here it was quite small. Now, years, later it is less small. Slow and stable, I can understand why my parents were attracted to it; after home, after Rwanda in 1994, it could have been paradise.

There is inexplicable magic in Namibia that slows things down, some spell which arrests movement and changes ambitions.I do not know how it happened, or when it did, but after a couple of years living in the country, the kinetic movement that seemed destined to drive us from one compass point to another slowed down—there is inexplicable magic in Namibia that slows things down, some spell which arrests movement and changes ambitions. After a few years, my parents bought a car and then house. We were put in schools, one sibling following another, with the clear plan of all of us completing our secondary education in Windhoek. We made friends. My parents entertained a small social circle. We became permanent residents, a status which put us on the path to citizenship. My family had cast its lot: in this desert we, tropical orchids, would find the grace to grow where we were planted. We would adapt to the local climate and adopt the necessary survival measures—becoming tough, succulent cacti, ambivalent about the harshness, always storing our hope for better times. I refused my pot—the itch for movement was still within me; the heat and the hammering of the times would not bend or shape me to the city’s will. As my teenage-hood approached, the yearning for escape intensified.

Many precede and many will follow

A young girl’s dreams no longer hollow

It takes the shape of a place out west

But what it holds for her, she hasn’t yet guessed

The best years of my teens seemed destined to arrive five years too late. According to the American television shows I watched while my hormones elongated my limbs, put some bass in my voice, and crossed my face with pimples, a high school romance was not on my immediate pubescent horizon. MTV’s TRL could have been beamed in from Pluto as far as my financial ability to visit New York was concerned. The local FM radio stations and their syndicated music chart shows were the only respite from my ennui. I systematically filled TDK cassettes (recorded in long play to extend the playing time) with carefully timed recordings. My friend and I traded them—whoever had that new-new or the hippest compilation was the coolest kid at school. Much later, MP3 CDs would become the norm before Apple’s iPods made music a solitary pleasure. The aural lonelinesses and longings we curated for each other as a form of connection ceased. We became interior beings, closed off—from parents, from each other. The world between our ears called to us, and we all looked for ways to answer.

What we wanted were wide open spaces… room to make mistakes… new faces. What we got was Windhoek.

Population: approximately 250 000.

Major landmarks and attractions: an old German fort.

Popular pastimes for teenagers: walking around aimlessly at the mall and sharing the one VHS recording of the And-1 basketball mixtapes between ourselves.

Chances of being the chair on which Britney Spears sat in (You Drive Me) Crazy: -100.

It was a miserable time in which to be a precocious teenager, to know there was a world outside Windhoek and Namibia, and not to be a part of it—globalization seemed to be happening everywhere except in our hometown. By then English had firmly become my first language, at first wrestling with Kinyarwanda and Swahili before finally erasing the latter and relegating the former to the periphery of my linguistic identity. I excelled in English at school; I raided the Windhoek Public Library for literature regularly; I argued with my parents in it; and I could firmly understand the messages coming through on the Rick Dees Weekly Top Forty: if you want to dance, my brodda, leave your street and go where dancehall is made; if you want to have the R&B and hip hop thug life, fam, leave Windhoek and make your way to New York or Atlanta; if you want a pop romance, leave Namibia and find the All Saints in London, bruv.

Like any first-generation immigrant’s child I yearned for movement defined by pleasure, not need. Among the many wanderlust-filled songs on the radio, I listened to a lot of music from The Chicks. Fly and Home were always on repeat. The Chicks sang of small town life, of girls longing for better, of women leaving to find themselves. All I wanted, really, as a young, black Rwandan-born teenager was a place where I could be anything except a young, black Rwandan-born teenager.

She traveled this road as a child

Wide-eyed and grinning, she never tired

But now she won’t be coming back with the rest

If these are life’s lessons, she’ll take this test

Where did I want to be?

Anywhere else.

*

The angst of my younger self amuses me when I come across journals of bad poetry I wrote while under the influence of Linkin Park and Evanescence—I think I was Rupi Kaur before Rupi Kaur was Rupi Kaur. My young writings contain the naivety of a boy convinced the best of the world lay outside of his reluctant homeland, that the world—whatever that means—is out there somewhere. But they also contain the scary convictions of the 33-year-old I am now: that the chance to once again enjoy unhindered movement, to not live in fear of handshakes or hugs, to have a birthday party with family and friends, to breath unprotected and raw air, will only be possible wherever privilege and access can be found.

Like any first-generation immigrant’s child I yearned for movement defined by pleasure, not need.Nineteen years after buying my last cassette I am in the same emotional zone I was when all I wished for was a computer with a CD-ROM burner and Nero software in lieu of a permanent relocation to the capitals of cool: I want out.

Where do I want to go?

Any place with COVID-19 vaccines.

What I want is to be in places where Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca jabs rain from the heavens like manna, where those of us who want to be vaccinated are separated from the anti-vaxxers by choice, not lumped together by scarcity and capitalist indifference. What I have, instead, is Windhoek, dependent on small Sinopharm and Covi-Shield donations from China, India, and any country that can spare them. The rest of the promised doses from COVAX are slow to materialize. Today, tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, next month—their estimated time of arrival remains uncertain even if the consequences of their delay are felt right here, right now, in frightening and depressing ways.

Much like my teenage years, when it felt like Namibia received things when they were no longer en vogue, it is scary and disheartening to realize in this desperate fight to contain the coronavirus’s spread and reach herd immunity, we are most certainly going to be one of the last countries to receive vaccines—this despite a small population of merely 2.5 million people (what many thought would be an advantage since herd immunity could be reached relatively quickly). Alarming news reports say poorer countries, of which Namibia is one despite its trappings of modernity, might only receive their doses later in 2021 with some countries only achieving widespread vaccination in 2023 or 2024. Unlike the US which proudly states its COVID-19 vaccination numbers on CNN’s ticket tape banner, there will be no cowboy to take us home.

*

Being the child of immigrants, I am quite familiar with the factors that fuel migration: stability, shelter, security, and a chance for social or economic progression—nobody leaves their home, where these things are typically hoped to be found, willingly. Anyone on a boat across the Mediterranean, a secret desert path or tunnel near the Mexican border, or a refugee processing center in Bangladesh finds themselves in those places under duress. I also know the luck of geography: if you are born with a British passport you can teach English all over South East Asia and lecture Kenyans and Ugandans about conservation; if you are German you can visit Namibia with enviable ease, expecting kowtowing hospitality from the former colony. Canadians can be vaccinated four times over. Anyone in migration knows the goal of the game: to land as close as possible to the source of power, to keep climbing the ladder—not to pause or stop halfway.

For a long time, my family found stability in Namibia. When I moved back to Windhoek after a failed attempt to live in Cape Town, in South Africa, I made peace with the feelings of failure that come with returning to small town life and put The Chicks on repeat. I did my best to make do. When I could be naturalized, I committed to embedding myself in the Namibian fabric. When I found happiness I married her. I finally pursued a career in literature and found some success. And when the chance to do something meaningful—that essential threshold of national sacrifice or contribution dangled over immigrants—presented itself, I co-founded the country’s first and only literary magazine. Whatever Namibia’s future story would be, I was determined to be a part of it. For a while it felt as though as I had found that long-discarded grace and reached some sort of settlement with Windhoek: if it could permit me to feel fulfilled in some way I would not despise it too much.

The immigrant math was clear: weak countries would be saved last, if at all.When COVID-19 began its progress around the world, prompting countries to close their borders, it was evidently clear any solution for the pandemic would prompt a scramble for it. Runt nations would be kicked off the teat. The immigrant math was clear: weak countries would be saved last, if at all. While not exactly 1994, the feeling of being trapped in a country with a spreading and deadly horror seemed familiar. At the onset of the pandemic, I remember feeling flat-footed, like the migration game had sidestepped me, leaving me and mine behind as it moved on to deliver a chance for salvation to everyone else who had carried on their upward and onward climb. The cardinal rule of migration had been broken: when you leave home you never stop moving. Ever.

My family did.

I did too.

I can almost hear Martie Maguire on the fiddle, Emily Strayer pluck the banjo, and Natalie Maines sing out the line carrying the blame: “There’s your trouble.”

Movement or migration, such as the one my family undertook early on in my life, is not a recipe for building anything long-term. At some point one has to stop, dig in their heels, and say the fated words: “no further,” “no more,” “upon this rock” and hope the rock yields water—failing a miracle, one has to grit their teeth and makes it so. My family did that—somehow we managed to navigate Namibia and its complex tribal strata, its politics, its racism, its xenophobia, its segregated neighborhoods, its inequalities, and its heat. Now I am wondering if it was the right choice. My wife and I ask ourselves if we were lulled into some false sense of security with the dreams and plans we had. We wonder if there was some sort of forecast we missed that predicted being trapped in a coronavirus-ridden country without clout. We are not ready to make nice with our diminished reality: economic precariousness, social isolation, and terminal uncertainty about what tomorrow may bring.

After a year of lockdowns, curfews, retrenchments, Zoom meetings, business liquidations, and deaths among friends and family, what we want is to be a long time gone, to fly out of here. We are ready to run.

Instead, we feel like we are trapped in Windhoek.

*

When my family arrived in Namibia in 1997 I had missed out on the beef-fueled Tupac and Notorious B.I.G. era of hip hop. Freshly desensitized to death by my experience of leaving Rwanda, I could not fathom how two dead men from the US could divide kids on the playground. They were dead. They were far away. And yet sides had to be and were chosen over these two dead black men whose words or appeal I could not understand as a non-English speaker. As my younger brother and I asked each other once: how could someone be both big and small at the same time?

What was immediately clear, though, was a pressing need to learn this language that was everywhere on the playground, to make friends, to blend in, and to find some sort of foothold in Namibian life. The radio became a focal point of our integration—we fought over who could record songs, or what stations we would listen to, and who would call in to the station to make a particular request. Country music, being slower and easier to listen to, became one of the first genres of English music we could truly understand. Shania Twain was a staple on the local airwaves, as was Hootie and the Blowfish’s “Let Her Cry,” Blake Shelton’s “Austin,” Lonestar’s “Amazed,” Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Achy Breaky Heart,” and Jewel’s “Down So Long.” While our age-mates made friendships through R&B and hip hop, my siblings and I rewound tapes and pressed play as we picked up English from Kenny Rodgers. As the smallness of my world dawned on me I found resonance in The Chicks’ discography and literature from and about other places. I dreamed of and plotted an escape with no return in accordance with migration’s rule: when you leave home you never stop moving.

That I am still here, in Windhoek, feels like some sort of cardinal sin.

Population: approximately 400 000.

Major landmarks and attractions: an old German fort and an ugly museum built using North Korean architectural principles.

Popular pastimes for adults: walking around aimlessly at the mall and sharing HBO, Hulu, Amazon Prime, or Netflix subscriptions with friends and family.

Chances of resuming some sort of normal life: unknown.

We are told that the vaccines will come. That once the West and the Global North have vaccinated their populations they will pay attention to the other compass points of the planet.

Surely, we are told, they cannot and will not leave us to our fates.

I am not so sure.

The vaccines will come, we are told. If they are, they are certainly taking the long way around.

“Wide Open Spaces” play count: 76.

______________________________________

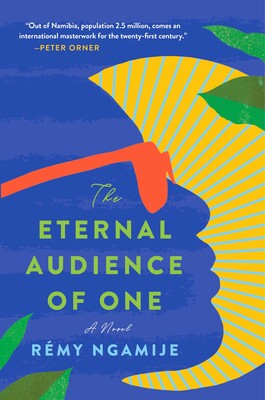

The Eternal Audience of One by Rémy Ngamije by is available now from Gallery/Scout Press.