Where There’s Smoke (Part 11)

Another batch this week of shorter appearances for fire-fighting gags from the theatrical front, plus a memorable educational entry from the newly-arising medium of television animation – which if you didn’t see on the small screen, you’ll probably remember from reissue in some school assembly. Theatrical offerings include a trio of Woody Woodpeckers in which Paul J. Smith falls into a proverbial rut of placing odd fire gags in the darndest places, and a theatrical appearance by the U.S. Forest Service’s famous fire-preventing bear.

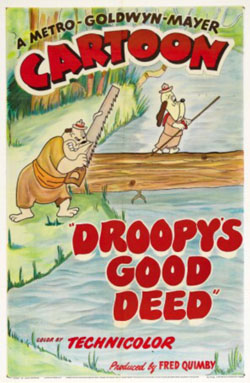

Upon the reminder of an observant blogger last week, I include, with apologies, a title inadvertently omitted from last week’s chronology Droopy’s Good Deed (MGM, Droopy, 5/5/51 – Tex Avery, dir.) This film always felt a little odd to me, maybe in part because of its cloistered status as a frequently censored rarity, its slightly offbeat plot that almost seemed like a second-string script that might have wound up in the reject pile like “Droopy Dog Returns” if something better had come along, and its strange animation of Droopy, with unusually-visible dentures whenever he speaks. Hobo Spike) of is it Butch? The names were interchangeable) impersonates a scout to get in on a “Best Scout” competition for a free trip to Washington to meet the President. (It might have seemed a more appealing motivation for Spike if there’d been a monetary prize at stake, However, I guess they didn’t think a boy scout should be interested in such mercenary pursuits.) Spoke sets up the usual array of dirty and potentially lethal tricks to win. In one scene, he enters a vacant log cabin, empties a kerosene lamp’s fluids on the floor, and sets fire to it. Fleeing outside and hiding behind a tree, Spike impersonates a woman’s screams for help to attract Droopy to the burning cabin. The heroic dog enters, then emerges a second later, carrying a beautiful young woman to safety. Spike goes ga-ga at the sight of the dame, and decides to run inside himself to check if there are others. One step inside, and the whole cabin foes up in smoke, leaving only a charred matchstick framework and the fireplace, with Spike also blackened from head to toe. Droopy returns, and although one can plainly see into the cabin from the lack of walls, takes the unnecessary step of opening the matchstick door frame to formally ask the sole occupant, “Hey, Blackie? Any more babes in there?”

Upon the reminder of an observant blogger last week, I include, with apologies, a title inadvertently omitted from last week’s chronology Droopy’s Good Deed (MGM, Droopy, 5/5/51 – Tex Avery, dir.) This film always felt a little odd to me, maybe in part because of its cloistered status as a frequently censored rarity, its slightly offbeat plot that almost seemed like a second-string script that might have wound up in the reject pile like “Droopy Dog Returns” if something better had come along, and its strange animation of Droopy, with unusually-visible dentures whenever he speaks. Hobo Spike) of is it Butch? The names were interchangeable) impersonates a scout to get in on a “Best Scout” competition for a free trip to Washington to meet the President. (It might have seemed a more appealing motivation for Spike if there’d been a monetary prize at stake, However, I guess they didn’t think a boy scout should be interested in such mercenary pursuits.) Spoke sets up the usual array of dirty and potentially lethal tricks to win. In one scene, he enters a vacant log cabin, empties a kerosene lamp’s fluids on the floor, and sets fire to it. Fleeing outside and hiding behind a tree, Spike impersonates a woman’s screams for help to attract Droopy to the burning cabin. The heroic dog enters, then emerges a second later, carrying a beautiful young woman to safety. Spike goes ga-ga at the sight of the dame, and decides to run inside himself to check if there are others. One step inside, and the whole cabin foes up in smoke, leaving only a charred matchstick framework and the fireplace, with Spike also blackened from head to toe. Droopy returns, and although one can plainly see into the cabin from the lack of walls, takes the unnecessary step of opening the matchstick door frame to formally ask the sole occupant, “Hey, Blackie? Any more babes in there?”

Some of our films this week are not available for embed online. If readers have a link to add to this post, please drop it in the comments below.

I’m No Fool With Fire (Disney, 12/1/55 – Bill Justice, dir.) – The success of Walt Disney’s debut into television, “Disneyland”, quickly led to the creation of the legendary daily series, “The Mickey Mouse Club” for ABC in 1955. Budgetary constraints of the day, and Disney’s insistence upon keeping up to a reasonable level the quality of his animation, prevented any thought of offering the daily episodes in an all-animated form, thus necessitating that the programming mostly rely upon the live-action antics of Jimmie Dodd, Roy Williams, and a troupe of junior “Mouseketeers” and their various guest stars, as well as additional live footage obtained from various sources, framed as the “Mickey Mouse Newsreel”. Remaining airtime would be filled with screenings of old cartoons (generally pre-1947), and many oft-repeated bumpers. However, Disney authorized the production of a series of new shorts, featured as intermittent specials in the line-up, framed in an educational vein. These shorts provided a comeback for a durable star from Disney’s feature work, and a talented veteran actor/singer/performer dating back to the dawn of sound. The character in question was Jiminy Cricket, Ward Kimball’s creation from the feature, “Pinocchio”. (For some great footage of Kimball relating the process of creation of the cricket, complete with original concept drawings, see the video, “Ward Kimball – The Inventive Animator – Jiminy Cricket” on Youtube’s “Dizographies” channel.) The cricket had already made one successful comeback as narrator for the compilation of featurettes, “Fun and Fancy Free” (1947), and his distinctive voice-over remained available for the re-hiring, in the form of veteran performer Cliff (“Ukelele Ike”) Edwards, whose talents still remained in fine form, despite the passage of approximately 30 years since his first major exposure to the public. Edwards would be featured in three alternating series of shorts for the Mouse Club – “You, the Human Animal”, featuring lectures on the workings of the body and its various senses; “Encyclopedia”, a sort of catch-all series for anything where supporting footage came to mind; and “I’m No Fool”, a series of educational lectures on safety. Each features a catch theme song performed by Edwards, with the “Fool” series and song perhaps the best remembered. Disney had the foresight to produce these shorts in color, allowing them to serve double and triple duty as theatrical releases in foreign markets, and as educational film rentals for generations to come here in the States.

I’m No Fool With Fire (Disney, 12/1/55 – Bill Justice, dir.) – The success of Walt Disney’s debut into television, “Disneyland”, quickly led to the creation of the legendary daily series, “The Mickey Mouse Club” for ABC in 1955. Budgetary constraints of the day, and Disney’s insistence upon keeping up to a reasonable level the quality of his animation, prevented any thought of offering the daily episodes in an all-animated form, thus necessitating that the programming mostly rely upon the live-action antics of Jimmie Dodd, Roy Williams, and a troupe of junior “Mouseketeers” and their various guest stars, as well as additional live footage obtained from various sources, framed as the “Mickey Mouse Newsreel”. Remaining airtime would be filled with screenings of old cartoons (generally pre-1947), and many oft-repeated bumpers. However, Disney authorized the production of a series of new shorts, featured as intermittent specials in the line-up, framed in an educational vein. These shorts provided a comeback for a durable star from Disney’s feature work, and a talented veteran actor/singer/performer dating back to the dawn of sound. The character in question was Jiminy Cricket, Ward Kimball’s creation from the feature, “Pinocchio”. (For some great footage of Kimball relating the process of creation of the cricket, complete with original concept drawings, see the video, “Ward Kimball – The Inventive Animator – Jiminy Cricket” on Youtube’s “Dizographies” channel.) The cricket had already made one successful comeback as narrator for the compilation of featurettes, “Fun and Fancy Free” (1947), and his distinctive voice-over remained available for the re-hiring, in the form of veteran performer Cliff (“Ukelele Ike”) Edwards, whose talents still remained in fine form, despite the passage of approximately 30 years since his first major exposure to the public. Edwards would be featured in three alternating series of shorts for the Mouse Club – “You, the Human Animal”, featuring lectures on the workings of the body and its various senses; “Encyclopedia”, a sort of catch-all series for anything where supporting footage came to mind; and “I’m No Fool”, a series of educational lectures on safety. Each features a catch theme song performed by Edwards, with the “Fool” series and song perhaps the best remembered. Disney had the foresight to produce these shorts in color, allowing them to serve double and triple duty as theatrical releases in foreign markets, and as educational film rentals for generations to come here in the States.

Each installment of “Fool” generally followed a formula. Repeated wraparound animation allowed Jiminy to introduce himself, refresh people’s memory as to his role as Pinocchio’s conscience, to help the puppet distinguish between the right way and the “foolish way”, and allow him to sing the theme song. The cricket would then proceed onto a library shelf, opening a book whose title announced the subject of the day’s safety lesson. Usually, opening pages of the book would illustrate how primitive cave man dealt with the danger of the subject, then trace developments forward in history as his wisdom and knowledge expanded. Here, a timid caveman peers from his dark cave at a lightning storm, which brings down a flaming branch from a tree top at his doorstep. He discovers the flame is warm and provides light, and takes it into his cave to cook food, garden weapons, and keep animals at bay from entering the cave at night. He guards the flame as a precious possession, but also discovers it can burn him if he steps too close. He also hits upon how to start a fire at will, by striking two stones of the right type together. Later man is shown fashioning uses for flame in pottery kilns, ovens for bronze weaponry, and in producing steam with the addition of water – leading to all manner of steam inventions in the industrial revolution. The film’s focus then shifts from historical to functional, teaching the three ingredients necessary to “the fire triangle” for a flame to burn – air, fuel, and heat.

Each installment of “Fool” generally followed a formula. Repeated wraparound animation allowed Jiminy to introduce himself, refresh people’s memory as to his role as Pinocchio’s conscience, to help the puppet distinguish between the right way and the “foolish way”, and allow him to sing the theme song. The cricket would then proceed onto a library shelf, opening a book whose title announced the subject of the day’s safety lesson. Usually, opening pages of the book would illustrate how primitive cave man dealt with the danger of the subject, then trace developments forward in history as his wisdom and knowledge expanded. Here, a timid caveman peers from his dark cave at a lightning storm, which brings down a flaming branch from a tree top at his doorstep. He discovers the flame is warm and provides light, and takes it into his cave to cook food, garden weapons, and keep animals at bay from entering the cave at night. He guards the flame as a precious possession, but also discovers it can burn him if he steps too close. He also hits upon how to start a fire at will, by striking two stones of the right type together. Later man is shown fashioning uses for flame in pottery kilns, ovens for bronze weaponry, and in producing steam with the addition of water – leading to all manner of steam inventions in the industrial revolution. The film’s focus then shifts from historical to functional, teaching the three ingredients necessary to “the fire triangle” for a flame to burn – air, fuel, and heat.

The film points from these to the differences in fighting a fire. For example, water may cool the heat of an average fire, but a grease fire can only be put out by covering and eliminating source of air. The value of backfires in controlling forest wildfires is also illustrated, as an example of removing fuel from the three-step equation to control a blaze’s spread. The final phase of the film follows the series’ standard formula, as Jiminy (in this episode converting his hat into a fireman’s helmet) draws with chalk on a blackboard outline drawings of an average boy (named “You”), and a dopey-looking taller gangly kid (dubbed with the title of “Fool”). To Jiminy’s song, the two chalk characters perform a contest of the comparative ways they handle potentially hazardous situations involving flame or items that might produce flame, with the Fool taking his lumps (disintegrating into chalk dust, etc.) while “You” performs things the correct way, and averts all danger. Jiminy presents a badge of merit with the cricket’s picture on it to “You” as the winner, then wraps the film up with a stock shot finale chorus of his song, dancing an “Off to Buffalo” exit for the iris out.

The film points from these to the differences in fighting a fire. For example, water may cool the heat of an average fire, but a grease fire can only be put out by covering and eliminating source of air. The value of backfires in controlling forest wildfires is also illustrated, as an example of removing fuel from the three-step equation to control a blaze’s spread. The final phase of the film follows the series’ standard formula, as Jiminy (in this episode converting his hat into a fireman’s helmet) draws with chalk on a blackboard outline drawings of an average boy (named “You”), and a dopey-looking taller gangly kid (dubbed with the title of “Fool”). To Jiminy’s song, the two chalk characters perform a contest of the comparative ways they handle potentially hazardous situations involving flame or items that might produce flame, with the Fool taking his lumps (disintegrating into chalk dust, etc.) while “You” performs things the correct way, and averts all danger. Jiminy presents a badge of merit with the cricket’s picture on it to “You” as the winner, then wraps the film up with a stock shot finale chorus of his song, dancing an “Off to Buffalo” exit for the iris out.

This film appeared in two editions, being updated a couple of decades later with interrupting insertion of live-action footage between a fireman and a group of children to provide information on smoke detectors and the like for the school assembly audience. This was a cheap way out rather than provide new animated sequences (although some new entire episodes in animated form were eventually produced on subjects not covered in the original series, with Hal Smith rather unsuccessfully attempting to match the vocal tones of Edwards’ wraparounds). By all means, stick with the superior structuring of the 1955 original.

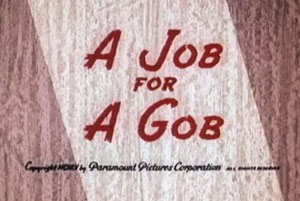

A Job for a Gob (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 12/9/55 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – on 30 days shore leave in the West, Popeye and Bluto spot a sign reading “Ranch Hand Wanted” at Olive’s ranch. The usual competition for the position takes place, with Popeye excelling at bronco busting and “humane” branding with a pogo stick and paint can. The job is Popeye’s, but vengeful Bluto vows, “I’ll give him a job to do”. He opens a corral gate and sets off a cattle stampede, then goes over the edge by committing arson and setting Olive’s barn on fire. Eating his spinach, Popeye first dispatches Bluto, by socking him skyward to the platform of a farm windmill, where his rear-end is paddled by the propeller blades. Then, he uproots the concrete cylindrical foundation of a ground well, and pours out its contents into a barn window to stop the blaze. Finally, he runs ahead of the charging steers, while carrying the well structure, and intercepts their path between the cattle and Olive, causing the cattle to crash into the side of the well structure. Their horns get stuck in the side of the well, and Popeye carries them all, upside-down protruding from the well wall, back to the corral, closing out a fine day’s work, for the iris out.

A Job for a Gob (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 12/9/55 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – on 30 days shore leave in the West, Popeye and Bluto spot a sign reading “Ranch Hand Wanted” at Olive’s ranch. The usual competition for the position takes place, with Popeye excelling at bronco busting and “humane” branding with a pogo stick and paint can. The job is Popeye’s, but vengeful Bluto vows, “I’ll give him a job to do”. He opens a corral gate and sets off a cattle stampede, then goes over the edge by committing arson and setting Olive’s barn on fire. Eating his spinach, Popeye first dispatches Bluto, by socking him skyward to the platform of a farm windmill, where his rear-end is paddled by the propeller blades. Then, he uproots the concrete cylindrical foundation of a ground well, and pours out its contents into a barn window to stop the blaze. Finally, he runs ahead of the charging steers, while carrying the well structure, and intercepts their path between the cattle and Olive, causing the cattle to crash into the side of the well structure. Their horns get stuck in the side of the well, and Popeye carries them all, upside-down protruding from the well wall, back to the corral, closing out a fine day’s work, for the iris out.

After the Ball (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 2/13/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) Lumberjack Pierre Bear runs a specialized lumber business – with a machine that devours whole trees and transforms them into rows of carved wooden bowling balls. (Strange. The wooden bowling ball fell out of use around 1906!) Pierre’s machine is actually a retread of the same machine that Woody Woodpecker used to carve broomsticks in Paul Smith’s first directing credit on the series, “Witch Crafty”. Anyway. Woody’s tree is felled and inserted into the machine, converting Woody’s apartment onto a hollow bowling ball. Woody takes care of central heating problems by sticking a rooftop-style smoke vent out of one of the bowling ball holes, and gets the home fires burning, emitting a stream of smoke into Pierre’s factory. Pierre smells the unfamiliar aroma, and runs to an emergency fire alarm box on the wall of his factory, breaking the glass. Out from the box pops a midget human fireman in full hat and slicker, who apparently lives full time inside the box. The little man carries a hose and nozzle, and begins feeding t into one of the holes of the bowling ball. Woody, however, drags the nozzle end out one of the other holes, polling the hose through until it reaches Pierre’s trousers, then inserts the nozzle inside Pierre’s belt. Pierre activates a water valve on the wall to start the fluids flowing – but winds up with his trousers bulging with a puddle of water inside. His pants are not pre-shrunk, and begin to tighten dramatically upon Pierre’s thighs. Before they can get too small, Pierre runs for the cover of a folding dressing curtain, and removes the garment, placing it in view upon a shelf. The trousers continue to shrink, shrink, until suddenly, they “pop” clear out of existence! Pierre retaliates by carrying Woody, atop the nozzle of the fire hose, over to a window, then opening the nozzle valve to shoot Woody high into the sky outside the factory.

After the Ball (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 2/13/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) Lumberjack Pierre Bear runs a specialized lumber business – with a machine that devours whole trees and transforms them into rows of carved wooden bowling balls. (Strange. The wooden bowling ball fell out of use around 1906!) Pierre’s machine is actually a retread of the same machine that Woody Woodpecker used to carve broomsticks in Paul Smith’s first directing credit on the series, “Witch Crafty”. Anyway. Woody’s tree is felled and inserted into the machine, converting Woody’s apartment onto a hollow bowling ball. Woody takes care of central heating problems by sticking a rooftop-style smoke vent out of one of the bowling ball holes, and gets the home fires burning, emitting a stream of smoke into Pierre’s factory. Pierre smells the unfamiliar aroma, and runs to an emergency fire alarm box on the wall of his factory, breaking the glass. Out from the box pops a midget human fireman in full hat and slicker, who apparently lives full time inside the box. The little man carries a hose and nozzle, and begins feeding t into one of the holes of the bowling ball. Woody, however, drags the nozzle end out one of the other holes, polling the hose through until it reaches Pierre’s trousers, then inserts the nozzle inside Pierre’s belt. Pierre activates a water valve on the wall to start the fluids flowing – but winds up with his trousers bulging with a puddle of water inside. His pants are not pre-shrunk, and begin to tighten dramatically upon Pierre’s thighs. Before they can get too small, Pierre runs for the cover of a folding dressing curtain, and removes the garment, placing it in view upon a shelf. The trousers continue to shrink, shrink, until suddenly, they “pop” clear out of existence! Pierre retaliates by carrying Woody, atop the nozzle of the fire hose, over to a window, then opening the nozzle valve to shoot Woody high into the sky outside the factory.

“Some days you just can’t get rid of a bomb!”

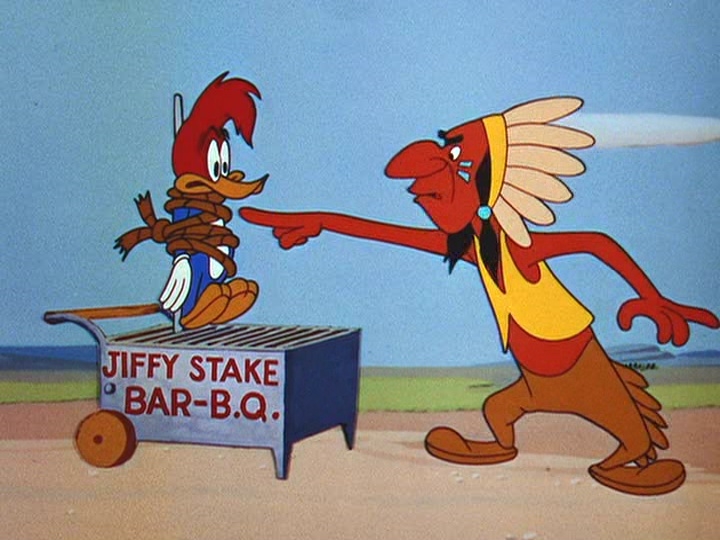

Chief Charlie Horse (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/7/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Woody’s latest occupation turns his natural talents to good use – as a wood-carver and sculptor in a small western town, where he specializes in the carving of wooden Indians. A renegade chief is wanted by the law, and hides out amidst Woody’s handiwork, posing as his latest wooden Indian. The sheriff is totally confused, almost offering Woody reward money for the statue, yet unable to tell the real chief when he sees him. The chief’s true identity, however, is detected by Woody – particularly when the chief keeps dodging the nailing-in of a “Sold” sign upon his person. But the chief puts Woody on the spot by capturing him, and tying him to a portable wheeled conveyance that looks like a backyard barbecue, but contains a special upright post for tying victims to above the grill, allowing for the burning of captives at the stake. To place himself into the mood, the chief pulls out a record player, placing on the turntable a record reading “Fire Dance”, and war-whoops around the barbecue while Woody’s toes begin to toast. However, Woody manages to slip one hand out of his bindings, to reach down and turn the record over to its flip side, reading “Rain Dance”, Changing the music is all that he needs to bring on a cloudburst and quench the fire. Ultimately, the confused sheriff again takes the wooden Indian into custody, and presents Woody with a sack of money as a reward. The chief reappears, and demands the sack from Woody at arrow-point. But he quickly returns it, dumping it at Woody’s feet as worthless, it being full of wooden nickels. As the chief leaves, Woody reveals his possession of the real sack, hidden behind his back, and tosses around the dollar bills in celebration, for the fade out.

Chief Charlie Horse (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/7/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Woody’s latest occupation turns his natural talents to good use – as a wood-carver and sculptor in a small western town, where he specializes in the carving of wooden Indians. A renegade chief is wanted by the law, and hides out amidst Woody’s handiwork, posing as his latest wooden Indian. The sheriff is totally confused, almost offering Woody reward money for the statue, yet unable to tell the real chief when he sees him. The chief’s true identity, however, is detected by Woody – particularly when the chief keeps dodging the nailing-in of a “Sold” sign upon his person. But the chief puts Woody on the spot by capturing him, and tying him to a portable wheeled conveyance that looks like a backyard barbecue, but contains a special upright post for tying victims to above the grill, allowing for the burning of captives at the stake. To place himself into the mood, the chief pulls out a record player, placing on the turntable a record reading “Fire Dance”, and war-whoops around the barbecue while Woody’s toes begin to toast. However, Woody manages to slip one hand out of his bindings, to reach down and turn the record over to its flip side, reading “Rain Dance”, Changing the music is all that he needs to bring on a cloudburst and quench the fire. Ultimately, the confused sheriff again takes the wooden Indian into custody, and presents Woody with a sack of money as a reward. The chief reappears, and demands the sack from Woody at arrow-point. But he quickly returns it, dumping it at Woody’s feet as worthless, it being full of wooden nickels. As the chief leaves, Woody reveals his possession of the real sack, hidden behind his back, and tosses around the dollar bills in celebration, for the fade out.

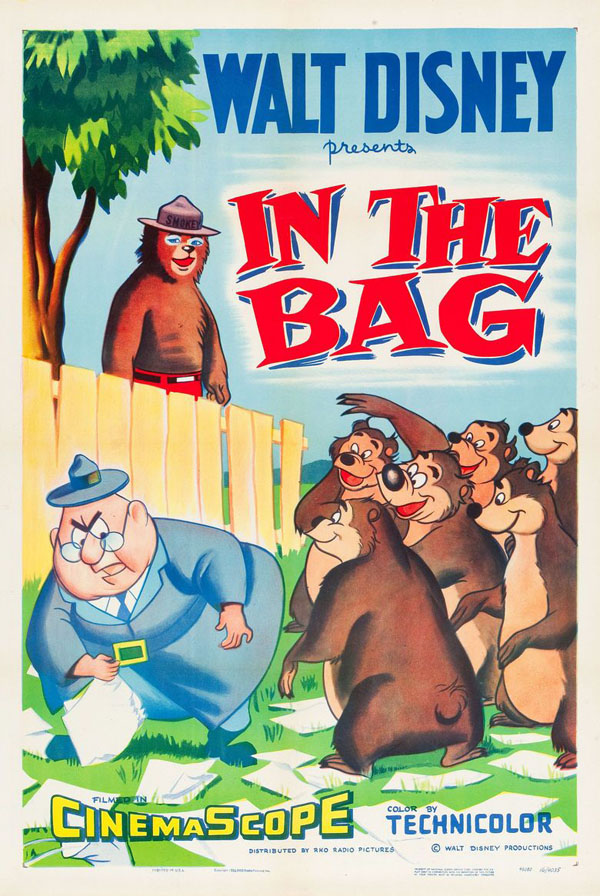

In the Bag (Disney/RKO, Humphrey Bear, 7/27/56 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Hannah’s last classic before leaving the employ of Disney. It is the end of the tourist season at Brownstone National Park, and Ranger Woodlore has been left with the usual problem – a park full of discarded litter. Grumbling and complaining at the tourists’ carelessness, Woodlore begins the arduous task of clean-up – then has a thought occurs to him. “Wait a minute. I’m the boss. Why should I clean up this mess?” He locates Humphrey Bear, and instructs him to call in the rest of the bears for a roll call, informing Humphrey that he has a “big surprise” for them. Within moments, the bears are assembled. “Now we’re gonna play a little game”, announces Woodlore. Woodlore draws out stripes on the dirt to divide the forest into sectors for each bear. He delegates Humphrey to pass out “gaming equipment” – consisting of large bags and sticks with pointed nail-tops on the ends. “A ones and a two…” begins Woodlore, breaking into a vigorous dance step, with a song about “First you stick a rag, put it in the bag (bump bump)…” The bears are thoroughly duped, and, caught up in the jive of the lively music, begin dancing with gusto, picking up stray papers and trash with every strut, twist and turn. Woodlore spurs them on by adding cymbal crashes provided by clanging trash can lids together. The “bump bumps” of the song’s rhythm are punctuated by enthusiastic bumping together of the bears’ posteriors as the dance continues. It seems Woodlore will get his way – until he is foolish enough to leave the bears to their own resources and try to catch forty winks in a hammock within the bears’ view, instead of continuing to lead the dance. The bears scratch their heads as they look at the refuse they have been piling up in their sacks, then catch on. One of them retaliates by lifting Woodlore gently from his hammock, then dumping him into a trash can. The rest of them empty the contents of their sacks back where they found them, and march away together, displaying ban-aids on their butt checks to cover sore spots from all the bumping. “Pretty poor sports”, remarks Woodlore. “This requires strategy.” Woodlore prepares a tasty dinner for the bears of chicken cacciatora, then rings a dinner bell. All the bears assemble at a picnic table for their nightly meal. However, Woodlore pulls rank, and breaks out the park rule book, citing a rule stating “He who does not clean up his section of the park, does not get any supper.” The bears realize Woodlore again has the upper hand, and all but Humphrey hit upon a quick-fix solution. In unison, each bear simply pushes the tall pile of debris within each marked sector of the park into Humphrey’s square, then returns to the picnic table to claim their meal. Perplexed Humphrey suddenly finds himself saddled with the task of disposing of the park’s entire supply of litter single-handed!

In the Bag (Disney/RKO, Humphrey Bear, 7/27/56 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Hannah’s last classic before leaving the employ of Disney. It is the end of the tourist season at Brownstone National Park, and Ranger Woodlore has been left with the usual problem – a park full of discarded litter. Grumbling and complaining at the tourists’ carelessness, Woodlore begins the arduous task of clean-up – then has a thought occurs to him. “Wait a minute. I’m the boss. Why should I clean up this mess?” He locates Humphrey Bear, and instructs him to call in the rest of the bears for a roll call, informing Humphrey that he has a “big surprise” for them. Within moments, the bears are assembled. “Now we’re gonna play a little game”, announces Woodlore. Woodlore draws out stripes on the dirt to divide the forest into sectors for each bear. He delegates Humphrey to pass out “gaming equipment” – consisting of large bags and sticks with pointed nail-tops on the ends. “A ones and a two…” begins Woodlore, breaking into a vigorous dance step, with a song about “First you stick a rag, put it in the bag (bump bump)…” The bears are thoroughly duped, and, caught up in the jive of the lively music, begin dancing with gusto, picking up stray papers and trash with every strut, twist and turn. Woodlore spurs them on by adding cymbal crashes provided by clanging trash can lids together. The “bump bumps” of the song’s rhythm are punctuated by enthusiastic bumping together of the bears’ posteriors as the dance continues. It seems Woodlore will get his way – until he is foolish enough to leave the bears to their own resources and try to catch forty winks in a hammock within the bears’ view, instead of continuing to lead the dance. The bears scratch their heads as they look at the refuse they have been piling up in their sacks, then catch on. One of them retaliates by lifting Woodlore gently from his hammock, then dumping him into a trash can. The rest of them empty the contents of their sacks back where they found them, and march away together, displaying ban-aids on their butt checks to cover sore spots from all the bumping. “Pretty poor sports”, remarks Woodlore. “This requires strategy.” Woodlore prepares a tasty dinner for the bears of chicken cacciatora, then rings a dinner bell. All the bears assemble at a picnic table for their nightly meal. However, Woodlore pulls rank, and breaks out the park rule book, citing a rule stating “He who does not clean up his section of the park, does not get any supper.” The bears realize Woodlore again has the upper hand, and all but Humphrey hit upon a quick-fix solution. In unison, each bear simply pushes the tall pile of debris within each marked sector of the park into Humphrey’s square, then returns to the picnic table to claim their meal. Perplexed Humphrey suddenly finds himself saddled with the task of disposing of the park’s entire supply of litter single-handed!

Humphrey tries every idea he can think of to get back to the dinner table. He first tries a forest version of weeping the mess under the rug, bu pushing it out of sight into a row of hedges. However, it is pushed back into view by a rabbit (Thumper?), who objects as the hedge happens to be his home. Humphrey then spots a book of matches among the trash, and, with a devilish look on his face, strikes one of them in an attempt to incinerate the pile. A large hairy foot, below an ankle surrounded by a cuff of blue-jeans, enters the frame and quickly stomps out the match flame until dead. Then a full shot reveals the foot’s owner – none other than Smokey the Bear. Hannah apparently lifts both image and voice track right out of advertising from the U.S. Forest Service, as the track sounds just like the official; voice of Smokey on the PSA’s as he says “Remember – Only you can prevent forest fires”, and his image consists of one still drawing from advertising posters, with mouth movements animated over it. Smokey even exist by merely raising and lowering the publicity still for his “steps”! Humphrey’s last resort is to dump all the trash down a hole in the ground – which he lives to regret, as violent vibrations alert him to the realization that the hole is really the geyser, “Old Fateful”. Humphrey leaps atop the hole in attempt to plug it, but has no effect, as both he and the trash are blasted skyward, the trash fragmenting to blanket the entire park once again. As Humphrey re-enters with a thud onto the ground, the ranger holds out to him a new bag and poker-stick. “Well, Hump, I’m truly sorry. But, remember the rules.” Humphrey ends the film by resuming the “bump bump” dance in a new round of picking up papers, in what promises to be a long, lo-o-o-ng dance, for the iris out.

Humphrey tries every idea he can think of to get back to the dinner table. He first tries a forest version of weeping the mess under the rug, bu pushing it out of sight into a row of hedges. However, it is pushed back into view by a rabbit (Thumper?), who objects as the hedge happens to be his home. Humphrey then spots a book of matches among the trash, and, with a devilish look on his face, strikes one of them in an attempt to incinerate the pile. A large hairy foot, below an ankle surrounded by a cuff of blue-jeans, enters the frame and quickly stomps out the match flame until dead. Then a full shot reveals the foot’s owner – none other than Smokey the Bear. Hannah apparently lifts both image and voice track right out of advertising from the U.S. Forest Service, as the track sounds just like the official; voice of Smokey on the PSA’s as he says “Remember – Only you can prevent forest fires”, and his image consists of one still drawing from advertising posters, with mouth movements animated over it. Smokey even exist by merely raising and lowering the publicity still for his “steps”! Humphrey’s last resort is to dump all the trash down a hole in the ground – which he lives to regret, as violent vibrations alert him to the realization that the hole is really the geyser, “Old Fateful”. Humphrey leaps atop the hole in attempt to plug it, but has no effect, as both he and the trash are blasted skyward, the trash fragmenting to blanket the entire park once again. As Humphrey re-enters with a thud onto the ground, the ranger holds out to him a new bag and poker-stick. “Well, Hump, I’m truly sorry. But, remember the rules.” Humphrey ends the film by resuming the “bump bump” dance in a new round of picking up papers, in what promises to be a long, lo-o-o-ng dance, for the iris out.

A coda to this film was that the dance number became so well remembered, a recording of it was released on ABC Paramount and Mickey Mouse Club records with new lyrics, which became retitled as “The Humphrey Hop”.

Calling All Cuckoos (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 9/21/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Herr Spring, German Black Forest clockmaker, needs a new cuckoo for his latest clock. (A stickler for authenticity, he seeks a live one rather than a wooden one.) Hunting in the forest and repeatedly calling out “Cuckoo”, he attracts the attention of Woody Woodpecker, who thinks he must be some kind of a nut. Woody decides to have some fun, and flattens out his topknot feathers to resemble a cuckoo, then darts zanily around the woods mimicking a cuckoo’s call. After many rounds of hide and seek with Herr Spring (including repeated encounters with a sleeping bear, always resulting in the clockmaker getting bashed on the head with a club for disturbing the bear’s slumber), Woody is finally caught, and shoved into the new clock, to work without supper. But Woody manages to engage in a game of hopscotch between one clock and another (is he pecking unseen escape holes in their back panels?), appearing at random out of the cuckoo’s doors of any clock closest to the clockmaker (and in one shot, out of three clocks at the same time). The clockmaker begins to lay in wait for Woody, setting various traps, then turning the clock hands to the hour 0 but Woody either makes each trap backfire (as in triggering off a mousetrap upon the clockmaker’s nose), or sets up his own counter-tricks from inside the clock, including one where a siren is heard as the clock door opens, and Woody emerges on the platform in a fireman’s hat and slicker, spraying Herr Spring in the face with a hose. Eventually, the hour of Twelve draws near, and Herr Spring runs for his earplugs to avoid the din of all the clocks going off at once. Woody seizes upon this opportunity to shove into the room the sleeping bear from outside. The bear is jarred to a frazzled awakening by all the birds popping out in his face, and, instead of using a club again upon the clockmaker, smashes the largest of the clocks over the clockmaker’s head, then makes his final exit. Woody appears again in the cuckoo door, mixing his laugh with more “cuckoo” calls, for the fade out.

Calling All Cuckoos (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 9/21/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Herr Spring, German Black Forest clockmaker, needs a new cuckoo for his latest clock. (A stickler for authenticity, he seeks a live one rather than a wooden one.) Hunting in the forest and repeatedly calling out “Cuckoo”, he attracts the attention of Woody Woodpecker, who thinks he must be some kind of a nut. Woody decides to have some fun, and flattens out his topknot feathers to resemble a cuckoo, then darts zanily around the woods mimicking a cuckoo’s call. After many rounds of hide and seek with Herr Spring (including repeated encounters with a sleeping bear, always resulting in the clockmaker getting bashed on the head with a club for disturbing the bear’s slumber), Woody is finally caught, and shoved into the new clock, to work without supper. But Woody manages to engage in a game of hopscotch between one clock and another (is he pecking unseen escape holes in their back panels?), appearing at random out of the cuckoo’s doors of any clock closest to the clockmaker (and in one shot, out of three clocks at the same time). The clockmaker begins to lay in wait for Woody, setting various traps, then turning the clock hands to the hour 0 but Woody either makes each trap backfire (as in triggering off a mousetrap upon the clockmaker’s nose), or sets up his own counter-tricks from inside the clock, including one where a siren is heard as the clock door opens, and Woody emerges on the platform in a fireman’s hat and slicker, spraying Herr Spring in the face with a hose. Eventually, the hour of Twelve draws near, and Herr Spring runs for his earplugs to avoid the din of all the clocks going off at once. Woody seizes upon this opportunity to shove into the room the sleeping bear from outside. The bear is jarred to a frazzled awakening by all the birds popping out in his face, and, instead of using a club again upon the clockmaker, smashes the largest of the clocks over the clockmaker’s head, then makes his final exit. Woody appears again in the cuckoo door, mixing his laugh with more “cuckoo” calls, for the fade out.

Pest Pupil (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Baby Huey), 1/25/57 – Dave Tendlar, dir.) – after being expelled from his first day in kindergarten, Baby Huey receives the services of a private tutor – a Germanic professor type, who assures Mrs. Duck that he will transform her boy into a genius. (He don’t know Huey very well, do he?) Among his curriculum is a music lesson on piano, with a junior piece that just happens to be titled “Fireman”. The professor foolishly asks Huey to play Fireman on the piano. Huey exits, returning wearing a fireman’s hat, and pushes the piano along while making to sounds of a fire engine: “Clang clang! Toot toot!” He climbs aboard the upright piano’s top lid, picking up the professor in the process, and they crash through the front door, rolling down a hilly street, while Huey continues with his sound effects, and stomps out discords with his feet on the piano keyboard. The piano crashes into a construction site at the base of the hill, upsetting a kerosene lantern, which lands inside the top of the piano alongside the professor, setting the sound box ablaze. Huey, thrown clear of the instrument, uproots the plumbing of a fire hydrant, rips the hydrant’s top off, and blasts a jet of water into the piano, flooding its inner chamber. A pair of small doors open, revealing the mechanism for a piano roll in the piano’s upper box, and the rollers begin to turn, as the flattened professor rolls out onto the keyboard, to the tune of “Ach Du Lieber Augustin.”

Pest Pupil (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Baby Huey), 1/25/57 – Dave Tendlar, dir.) – after being expelled from his first day in kindergarten, Baby Huey receives the services of a private tutor – a Germanic professor type, who assures Mrs. Duck that he will transform her boy into a genius. (He don’t know Huey very well, do he?) Among his curriculum is a music lesson on piano, with a junior piece that just happens to be titled “Fireman”. The professor foolishly asks Huey to play Fireman on the piano. Huey exits, returning wearing a fireman’s hat, and pushes the piano along while making to sounds of a fire engine: “Clang clang! Toot toot!” He climbs aboard the upright piano’s top lid, picking up the professor in the process, and they crash through the front door, rolling down a hilly street, while Huey continues with his sound effects, and stomps out discords with his feet on the piano keyboard. The piano crashes into a construction site at the base of the hill, upsetting a kerosene lantern, which lands inside the top of the piano alongside the professor, setting the sound box ablaze. Huey, thrown clear of the instrument, uproots the plumbing of a fire hydrant, rips the hydrant’s top off, and blasts a jet of water into the piano, flooding its inner chamber. A pair of small doors open, revealing the mechanism for a piano roll in the piano’s upper box, and the rollers begin to turn, as the flattened professor rolls out onto the keyboard, to the tune of “Ach Du Lieber Augustin.”

More from the late days of theatrical cartoons, next week.